Rawls on Libertarianism

Overview

Rawls walks his readers through a series of “systems” concerning the distribution of wealth and opportunities. These systems are defined by how they combine different interpretations of two phrases in Rawls’s second principle of justice. Two phrases that each have two interpretations yields four systems.

The system that most resembles Nozick’s libertarianism, the System of Natural Liberty, is consistent but wrong, in Rawls’s opinion. He believes that it is unfair for your course in life to be determined by your family’s social class or your natural abilities. The System of Natural Liberty does nothing to correct or compensate for either source of unfairness.

Two of the other systems make partial attempts to deal with the problem of morally arbitrary influences. Liberal Equality seeks to correct the social causes of inequality through an educational system that seeks to ensure that everyone has the same opportunities in life as those with similar natural talents, regardless of their social background. Natural Aristocracy does nothing to correct for the social causes of inequality but it compensates those who have less by implementing the Difference Principle. That means that inequalities in wealth and opportunity will be allowed only if they improve the wealth and opportunities of the worst off class.

Rawls believes that the case for either Liberal Equality or Natural Aristocracy is unstable. If you are convinced that the distribution of goods should not be influenced by morally arbitrary factors, why address only some of those factors rather than addressing them all as Democratic Equality does? Someone who moved from Natural Liberty to one of these other systems would not stay there because the line of thinking that leads away from Natural Liberty also leads beyond them. Thus, Rawls concludes, only Democratic Equality is both consistent and correct.

What is the Difference Principle?

The Difference Principle holds that a society should allow inequality in wealth if and only if that inequality works to the advantage of the worst off class. The idea is that people will produce more only if they are allowed to keep at least part of what they produce. The poorest people, in turn, are better off living in a more productive society that is unequal than they would be in one that was strictly equal. They benefit from the greater production that follows from inequality. So the Difference Principle allows inequality because it makes everyone better off. But it only allows inequality so long as the worst off benefit. Once greater inequality ceases to benefit the worst off class, it is no longer allowed; it would be confiscated by taxes or discouraged by regulations.

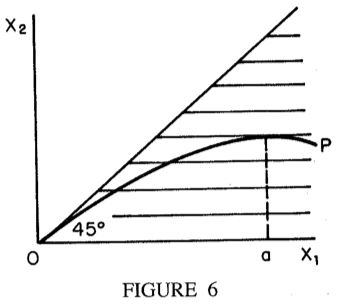

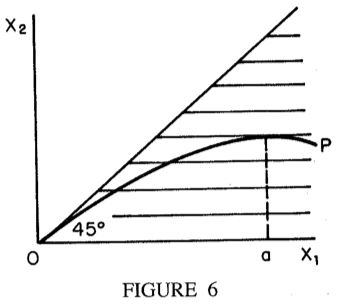

This figure illustrates how the Difference Principle works.

The two axes represent wealth that goes to representative members of different classes: X1 and X2.

The origin represents what society would produce if wealth were distributed equally between those classes. It is not nothing; it’s just where the graph starts.

The curved line (OP) represents what society could produce if it allowed inequality. In this case, the X1 class gets more wealth than the X2 class. That is why the curved line is below the 45 degree line: it moves more to the right than it moves up.

X1 gets wealthier as the line goes to the right and X2 gets wealthier as the line goes up. When the curved line is moving up and to the right, both X1 and X2 benefit. A society following the Difference Principle would seek to hit point a. That is where the line reaches its highest point on the Y axis, meaning that is the point at which inequality benefits the members of the worst off class the most. Anything to the left or right of a would leave people like X2 worse off than they would be at point a.

What Would a Libertarian Say in Response?

Rawls’s only significant discussion of libertarianism comes in the informal part of the book. By “informal,” I mean the part where he took himself to be explaining his ideas rather than arguing for them. The official arguments come later. They depend on what the parties in the original position would choose.

But the parties in the original position aren’t asked to consider libertarianism. The part that we talked about today gives Rawls’s reasons for not asking them to consider libertarianism.

If I were Nozick, I would say that Rawls’s assumption is wrong and the unfairness of life is only a metaphorical expression. As Nozick sees it, only people can be unfair. No one treats you unfairly if you do not succeed because you lack talent and it is not unfair for parents to favor their children. So, in Nozick’s opinion, neither the natural nor the social sources of inequality are necessarily unfair or morally arbitrary.

That, in my opinion, is the argument that Rawls has to beat.

What Would a Radical Critic Say?

If I were a radical critic of capitalist society, one thing I might do is question Rawls’s assumption that inequality is necessary for a productive society.

In Figure 6, the line OP represents what a society could produce. The origin represents the goods available in a perfectly equal society. (It is at coordinate 0,0 on the graph, but that does not mean it is nothing; it’s just where the graph starts.) The amount of goods rises (it moves up and to the right) as more inequality is allowed (the OP line moves away from the 45 degree line).

The assumption is that people will produce more if and only if they are allowed to keep at least a part of what they make. That is why you get inequality: the more productive wind up with more than the less productive do.

But a radical critic might question whether this is really so. Could people be motivated to produce for reasons other than gain? Could they be motivated by artistic reasons, social solidarity, or something else? It may be true that incentives are needed to motivate people to work in our society. But, a radical critic may say, that does not mean that all societies must work this way. In a different social order, people would have different motivations.

Speaking for myself, I think Rawls is probably right. But he hasn’t shown that he is right. He has just drawn a graph that assumes that inequality is necessary for a productive society.

Do People Keep What They Make?

Suppose you think that people who work harder (or more productively) should get more than those who don’t. That is something that most of us believe. Rawls agrees, in a way. People like X1 have more because they produce more for society while people like X2 have less because they produce less.

But Rawls is unlike Locke. He does not think that there is a natural relationship between working and having rights to keep what you produce. People like X1 get to have more because giving them more works to the advantage of the worst off class. When letting them keep what they produce no longer benefits the worst off class, they no longer get to do so. In that way, Rawls’s views are a bit like utilitarianism. Your economic rights are derived from considerations of the social good; they are not natural rights.

Another way to put that is to say that Rawls is going to insist on maximizing the resources going to x2 regardless of why x2 is worse off than x1. It doesn’t matter if x2 is worse off due to factors beyond his control or if x2 is just lazy and deliberately chooses not to work because he knows that he is guaranteed to wind up at point a.

Why not natural aristocracy?

Rawls thinks the equal opportunity should come before the difference principle. That means that he thinks society should devote its resources to ensuring that “those with similar abilities and skills should have similar life chances” first (Rawls 1999, 63). It should use the resources it has left to make the position of the worst off class as good as it can be; raising point a as high as it can go.

Of course, the two projects often go together. A society can raise point a by developing the talents of its members so that they are more productive. So a society devoted to the difference principle will also do quite a lot to counteract the influence of social class on the development of talents. But equality of opportunity as Rawls understands it is very demanding. At some point, I suspect that the resources needed to move a society closer to equal opportunity would go to the educational system at the expense of improving its productive capacity.

James asked why this is so important for Rawls. (Later, he asked why the parties in the original position would care about equal opportunity; that’s a good way to put the point.) I think he’s right and that Rawls should have stopped with Natural Aristocracy. A Natural Aristocracy follows the difference principle: it seeks to make the people at the bottom as well off as they possibly can be without being committed to equal opportunity.

Why? Well, Rawls himself argued that the distribution of natural talents, abilities, and skills is “arbitrary from a moral point of view” (Rawls 1999, 63). Why should it matter whether your success or failure is due to natural or social causes? If you fall to the bottom class in society because you have little natural talent or because your society did not develop your talents, it should all be the same from the ‘moral point of view.’ Neither one is more fair or unfair to the person behind the talents. So the only thing left to do would be to ensure that those at the bottom have as much as possible.

Here’s Milton Friedman making the basic point:

Inequality resulting from differences in personal capacities, or from differences in wealth accumulated by the individual in question, are considered appropriate, or at least not so clearly inappropriate as differences resulting from inherited wealth.

This distinction is untenable. Is there any greater ethical justification for the high returns to the individual who inherits from his parents a peculiar voice for which there is a great demand than for the high returns to the individual who inherits property? …

Most differences of status or position or wealth can be regarded as the product of chance at a far enough remove. The man who is hard working and thrifty is to be regarded as ‘deserving’; yet these qualities owe much to the genes he was fortunate (or unfortunate?) enough to inherit. (Friedman [1962] 1982, 164–66)

I’m not saying that I am as opposed to equality opportunity as Friedman seems to be. I’m with Michael: I think society should help people develop their skills and talents. My point is only that I don’t think Rawls has an explanation of why equal opportunity is valuable and, in fact, his arguments undercut the case for thinking that it matters. It’s a point about what the arguments show, not a point about what I believe.

Main points

Here are the terms and concepts you should know or have an opinion about from today’s class.

- Rawls’s four systems: Natural Liberty, Liberal Equality, Natural Aristocracy, Democratic Equality.

- What Rawls means by “factors so arbitrary from a moral point of view” (Rawls 1999, 63).

- Figure 6 and the Difference Principle.

References

Friedman, Milton. (1962) 1982. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rawls, John. 1999. A Theory of Justice. Revised edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.