What is innate, according to Leibniz?

What notions and doctrines are innate, according to Leibniz? His best examples concern what he calls “common notions” in mathematics. These come from Euclid’s Elements.

- Things which equal the same thing also equal one another.

- If equals are added to equals, then the wholes are equal.

- If equals are subtracted from equals, then the remainders are equal.

- Things which coincide with one another equal one another.

- The whole is greater than the part.

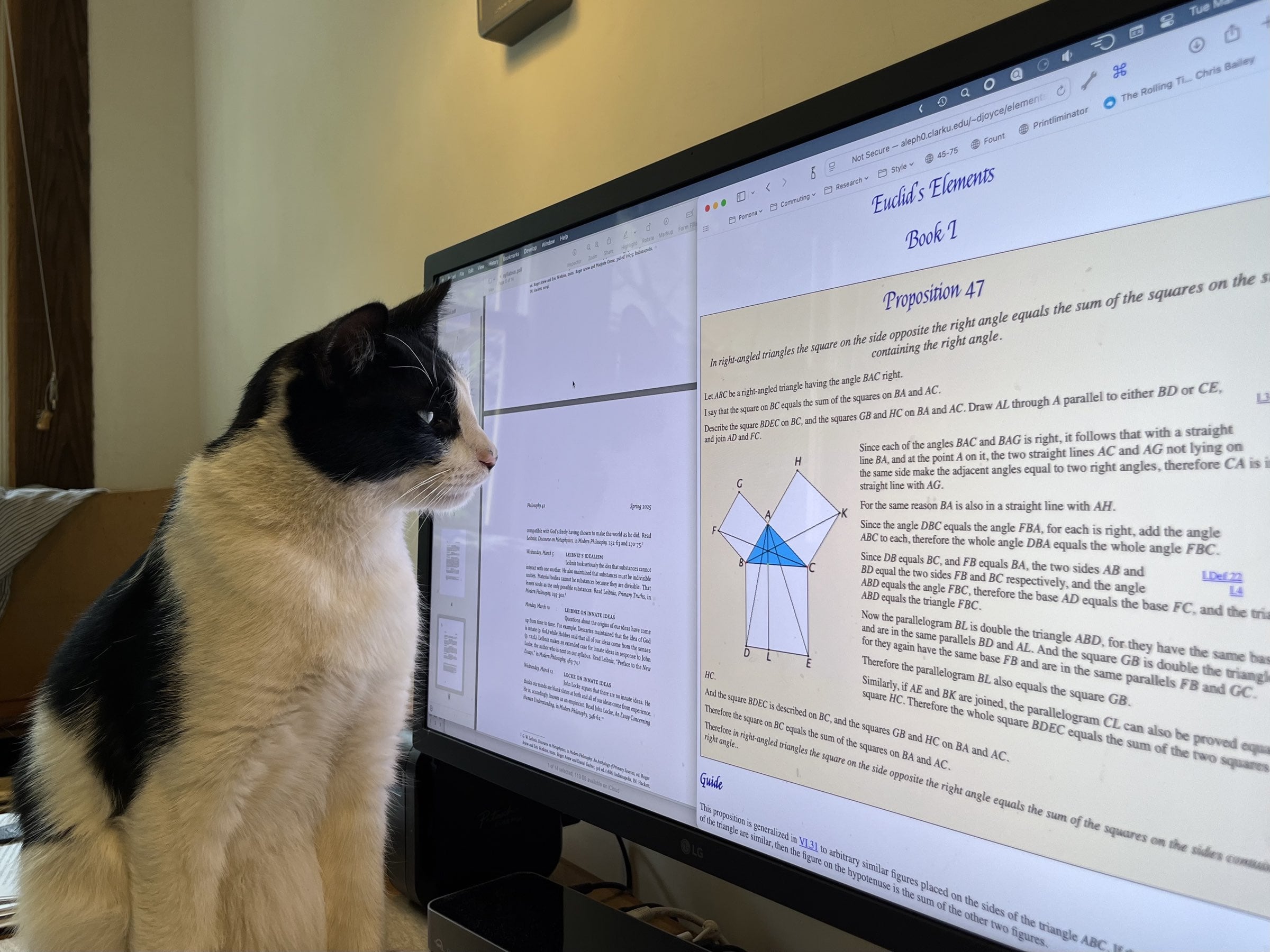

Leibniz is especially impressed by our ability to recognize necessary truths. Experience only gives us experience of some, say, right triangles. How can it show us that the Pythagorean Theorem will be true for all of them?

Leibniz believes that geometry, logic, metaphysics, and morals are all areas of knowledge that concern necessary truths (Leibniz 2019, 464R).