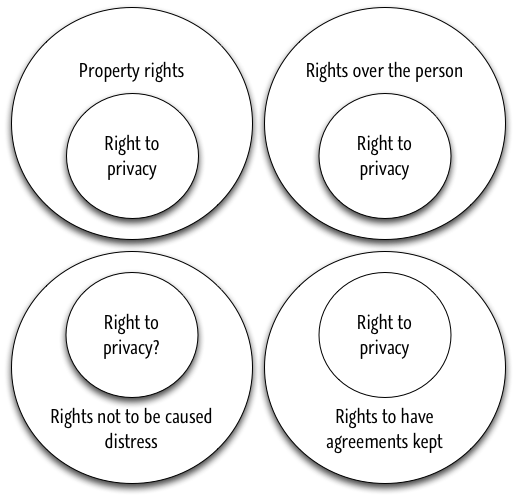

Thomson proposes what she calls a “simplifying hypothesis” about the right to privacy, namely, that the right to privacy is derived from other rights. In particular, she believes that the right to privacy that we actually have is derived from property rights and the right over the person.

I was chiefly interested in saying how Thomson’s views differ from those articulated by Warren and Brandeis’s article and Brandeis’s dissent in Olmstead v. United States.

Thomson’s simplifying hypothesis is that the right to privacy is made up of parts of other rights, especially the right to property and the right over the person.

I finally came up with a way of illustrating this that isn’t idiotic. Third time’s the charm!

Why is there a question mark in the right not to be caused distress circle? Because Thomson’s opinions are complex. She thinks that it is possible for there to be a right to privacy there but that, as a matter of fact, there is not such a right. And I added the right to have agreements kept because that is another right that she thinks is relevant to privacy: if I tell you something on the condition that you agree to keep it secret, my right that you keep it secret is a privacy right. I will explain in the next section

Thomson takes up the question about what rights we have to control information in the seventh section (Thomson, 307–10). Since that is the heart of the right to privacy according to Brandeis and Warren, this is where we can find points of agreement and disagreement.

She says that we have two kinds of rights concerning information:

Rights to property and the right over the person take care of the first category, that certain steps not be taken to find out facts. The steps that cannot be taken are those that violate the rights to property or the person. Thus information cannot be gathered by an X-ray device that looks into your house and it cannot be gathered through torture, coercive threats, or spying (Thomson, 307–9).

What about the second category, that certain uses not be made of facts? Information cannot be used if it involves breaking a promise: if I tell you something on the condition that you not spread it, I have a right that you not spread it (Thomson, 309). And I assume information that was taken in violation of a property or personal right cannot be used.

But what if you came by information innocently and without conditions? Could you publish it? Warren and Brandeis said that, in at least some cases, the answer is no because the right to privacy gives the person whose privacy would be invaded by publication the right to control that information by blocking publication or recovering compensatory damages.

Thomson thinks there is a possible case for this conclusion but that it is not an actual case. That is, she believes the right against publication would come from the right not to be caused distress. Unlike Sydney, she thinks that there is a right not to be caused distress. But, she thinks, that is not enough to show that there is a right against publication of private information because the public interest in having a press free to print all sorts of information “mostly” outweighs the individual interest in avoiding the distress that comes from the publication of private information (Thomson, 309–10).

So does she agree with Warren and Brandeis? Sort of yes but mostly no. “Sort of yes” because she offers her own interpretation of Warren and Brandeis’s argument: there is a right to privacy that is part of the right not to be caused psychological distress. Warren and Brandeis did emphasize the psychological importance of privacy in making their case. However, I would think that they would say that whether an infringement causes distress or not is incidental to the right. That is, I would have thought that their view is that I have a right to control the information in my letters, regardless of whether its disclosure would be upsetting to me or not. It’s hard to see how the man who wanted to keep the catalog of his gems secret would have been distressed by its publication, after all (Warren and Brandeis, 202–3). More generally, Warren and Brandeis tried to show that there is a right to privacy distinct from property and other rights. Thomson is trying to show that this is not so and that privacy rights are just parts of other rights. Finally, Thomson doesn’t think there actually is a right to privacy that allows an individual to prevent the publication of private information. Warren and Brandeis, of course, thought there is such a right. So, “mostly no.”

That is what I meant in saying that Thomson is primarily interested in how the information is acquired. The right to privacy, as she sees it, comes into play when the process of acquiring information violates a right, like the rights to property or the person, or when the information is acquired in a way that includes a limit on its use, like a promise not to publish it. She’s willing to concede that there could be a case for a right against publishing information that is innocently acquired. But this is only hypothetical since she doesn’t think there typically is such a case.

I added that it seemed to me that the same point about the press would apply equally well to information acquired by illegitimate means. The public’s interest in gaining information from the press could be strong enough to allow the press to override property rights, rights to the person, and contractual rights as well. After all, the press sometimes does obtain information in dodgy ways. Michael didn’t think that she would deny that and maybe he’s correct. But she didn’t say it: the only part of the right to privacy to which the point about the press is applied is the one having to do with using the right against being caused distress to suppress publication of private information. I don’t know if that reflects a genuine opinion or if it was simply something she neglected to mention.

Finally, let’s not forget about Brandeis’s dissent in Olmstead. There, the information in question is being kept away from the state, not the public and press. Thomson didn’t address that sort of case. I assume she would approach it in the same way by asking whether the public’s interest in catching criminals overrides the rights to property and person of those who would be spied on. (Remember that includes both innocent and guilty.)

At the end of the article, Thomson says something a little different about the publication of information that was innocently acquired. In the paragraph I’m about to quote, she says that a right against publication would contradict her simplifying hypothesis; earlier she had said that such a right would be compatible with the hypothesis on the grounds that the right could be assimilated to the right against being caused distress.

“Some acquaintances of yours indulge in some very personal gossip about you. Let us imagine that all of the information they share was arrived at without violation of any right of yours, and that none of the participants violates a confidence in telling what he tells. Do they violate a right of yours in sharing the information? If they do, there is trouble for the simplifying hypothesis, for it seems to me there is no right not identical with, or included in, the right to privacy cluster which they could be thought to violate. On the other hand, it seems to me they don’t violate any right of yours. It seems to me we simply do not have rights against others that they shall not gossip about us.” (Thomson, 311–12)

I don’t know why she didn’t say that the right not to be caused distress would explain the right not to be gossiped about. If the distress caused by gossip is great enough, then we have a right to privacy here. If not, then we don’t. Gossip usually isn’t all that distressing, so we usually don’t have right to privacy that blocks gossip. That’s what I would have expected her to say and I don’t know why she didn’t.