We talked about Thomson’s “simplifying hypothesis” that the right of privacy is not a distinct right on its own but is rather derived from other rights.

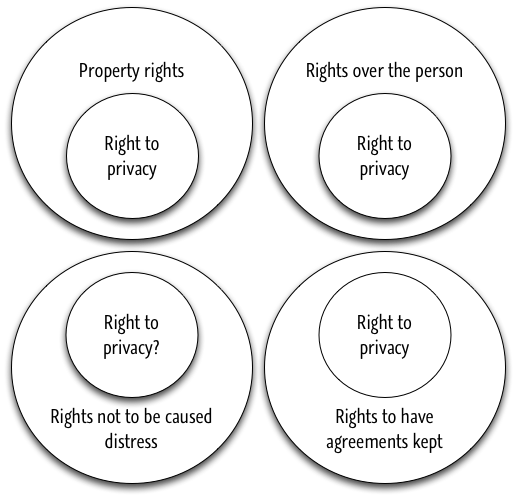

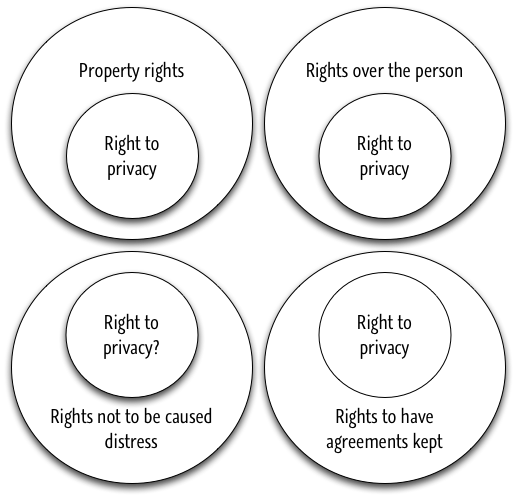

Here’s an illustration of the simplifying hypothesis: privacy shows up as a subset of other rights. The hypothesis is that it only shows up within other rights and never on its own.

Angela came right out of the box and asked what unites all the various instances of the right to privacy? That is, how do we identify the small circles labeled “privacy” and distinguish the rights in those circles from the other rights in the big circles that have nothing to do with privacy?

I don’t know how Thomson would answer that. I suppose that her project is motivated by the thought that there is no satisfying answer. The little circles may be identified simply by being what people commonly call privacy rights, even though there is no theoretically satisfying way of explaining what they all have in common. But that’s just my guess about what she would say.

The closest that Thomson comes to something like Warren and Brandeis’s position is in the seventh section of her article. That section is about private information. In it, she distinguished between rights against certain means of discovering information (such as torture) and rights that certain uses not be made of facts (such as publication). The latter is what Warren and Brandeis said the right to privacy consists in: the right to control the publication of private information and images.

For Thomson, the right to control the use of information is derived from the right not to be caused distress. As Aaron pointed out, the right not to be caused distress has to be carefully defined: it can’t just be the right not to take offense at anything, no matter how eccentric your feelings are. Thomson is willing to say that there is such a right. But she is reluctant to say that it gives a right to privacy. That is because she thinks it would be trumped by the public’s right to the information that the press deems newsworthy.

So there might have been a right to privacy such as the one Warren and Brandeis described. But, in fact, there is not.

I asked why it was obvious that the right to privacy would have to be derived from the right not to be caused distress. The right to control my property doesn’t have to be derived, why does the right to control private information have to be derived? At least, that is what Warren and Brandeis would ask.

Sally said she thought Thomson’s reason for rejecting Warren and Brandeis’s position was spelled out in the examples at the beginning of the article. In those examples, there are different cases in which people acquire some piece of information, such as the information about the fight. But, according to Thomson, the right to privacy is only violated in some of those cases and not others. That contradicts Warren and Brandeis’s opinion that the right to privacy is violated whenever private information is in the wrong hands.

That’s a good point. If I were Warren and Brandeis, I suppose I would say one of two things in response. First, I might try to say that the right to privacy is violated if the person who overhears the fight publishes information about the fight. No right can prevent you from overhearing the fight, after all. Second, I might say that the fighters have effectively lost control of the information about their fight. By yelling in public, they made their private information public. But I have to think about this some more before I know what I think. Good point, Sally!