We talked about Thomson’s “simplifying hypothesis” that the right of privacy is not a distinct right on its own but is rather derived from other rights.

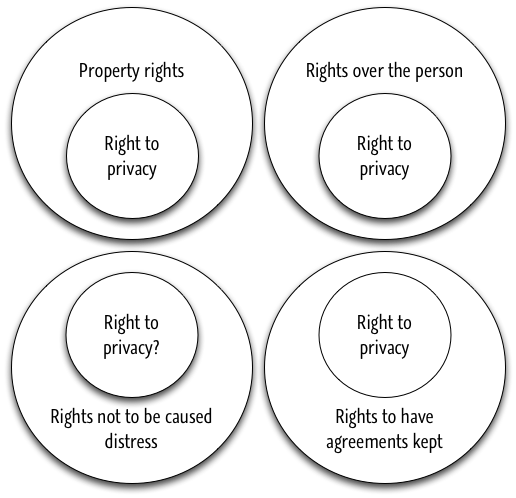

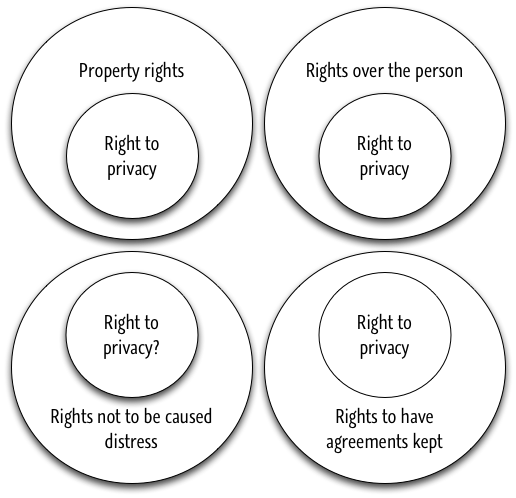

Here’s an illustration of the simplifying hypothesis: privacy shows up as a subset of other rights. The hypothesis is that it only shows up within other rights and never on its own.

You might ask, “so what do all the little privacy circles have in common, such that it makes sense to use the same word for them?” I think Thomson would say that there is no illuminating answer to that question. The simplifying hypothesis simplifies the right to privacy by giving up on the attempt to identify a distinct, unified right to privacy. The idea is that it it more accurate to describe the wide array of cases we put on the board last time as instances of other rights than it is to try to squeeze them into one box.

Even though she despairs of a unified theory of privacy rights, Thomson does think there are some useful generalizations. For instance, some of the rights that make up what we loosely call the right to privacy are rights that limit how others can acquire private information (Thomson 1975, 307–8) while others are rights governing how others can use information (Thomson 1975, 310–12).

For example, she thinks there is a general right not to be looked at and that this right is waived by a person who is walking in the street but that it is not waived by a person who is inside her house. Consequently, if you take unusual steps to look at people in their houses, like using an x-ray machine, you violate their right to privacy. This is an example of how the right to privacy governs the acquisition of information. (Similarly, property rights convey the right to prevent others from looking at things. The privacy right derived from property rights is invaded when someone tries to defeat the normal means used to prevent others from looking at one’s property, such as keeping it in your house.)

Rights governing the use of information are trickier. Thomson says that if there is such a right, it has to be derived from the right not to be caused distress. But this seems to be a merely hypothetical point for her. She thinks the right not to be caused distress is outweighed by the freedom of the press, so there is really no privacy right against publication of information in the press (Thomson 1975, 310). And she does not think that there is a right that private individuals not gossip about you, no matter how hurtful their doing so may be (Thomson 1975, 311–12).

So there is space in Thomson’s analysis for the cases that Warren and Brandeis thought were central, namely, rights to control the publication of personal information. But it is merely logical space for her.

We were not happy at all with either of the more general rights that, Thomson claimed, the right to privacy is derived from.

Leah did not think there is any such right as the right not to be looked at. She thinks it goes the other way around: the right to privacy explains when you can’t be looked at, not that there is a right not to be looked at that is not waived only when you are in private.

Gabe and others were unhappy about the right not to be caused distress. We settled on a nice way of making the point. I might cause you distress in lots of ways. For instance, I could deliver bad news or I could publish your diary on the internet. No one thinks the first is a violation of your rights, so it is reasonable to think that there are rights against certain ways of being caused distress rather than one general right against being caused distress. Sydney proposed a nice alternative: there is a right against being bullied. That sounds a lot better.

My contribution to the discussion was to say that I did not think the right to privacy had to be derived from the right not to be caused distress. The right to privacy is valuable because it enables us to avoid being caused distress and we are distressed when it is violated. But it doesn’t follow that the right is derived from the right not to be caused distress. I proposed an analogy with property rights. It is valuable to us to have property rights that give us exclusive control over material things. But property rights do not lapse when the things we own are not important to us. To put it another way, my rights to control material things do not have to be derived, so why does the right to control private information have to be derived? At least, that is what Warren and Brandeis would ask.

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1975. “The Right to Privacy.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 4 (4): 295–314.