Figure 6 from John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice

We discussed Waldron’s criticism of Rawls’s difference principle. Rawls had argued that the parties in the original position would select the difference principle rather than utilitarianism because they would know they are required to make a final commitment to a set of principles and they would fear that they might not be able to keep their commitment if they wound up as losers in a utilitarian society.

Waldron asked what the parties would pick if they had to choose between Rawls’s principles and utilitarianism with a floor of a guaranteed social minimum. In that choice, the fear of being losers wouldn’t be a reason to prefer Rawls’s principles since, by hypothesis, the guaranteed minimum prevents anyone from losing. And there appears to be a lot to gain from choosing to maximize average utility for everyone above the floor when compared with Rawls’s principles.

Waldron’s social minimum is an absolute standard that is based on what people need. Rawls’s difference principle is a distributive or relative standard that is based on where the poor stand relative to the rich. The difference is that a society committed to Rawls’s principles has to redistribute from rich to poor as the rich get richer. A society committed to Waldron’s social minimum only has to ensure that the needs of the poor are met; it is not committed to doing anything in particular about the gap between the rich and poor.

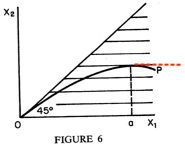

In order to illustrate the point, I returned to our old friend: Figure 6 (Rawls 1999, 66). This charts the share of primary social goods (which I will just call “wealth”) held by two groups. The chart is meant to illustrate the effects of incentives: the people in X1 will produce more if they are allowed to earn more than a strictly equal share and this will make the people in X2 better off even if it means they will have less than the people in X1.

Figure 6 from John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice

The difference principle is a relative standard because it treats inequality as undesirable in itself. It permits inequality, but only so long as it is necessary to raise the wealth of the worst off class. In Figure 6, inequality is permitted only as long as the worse off group (X2 in this graph) is made better off. Once the society hits point a, no additional inequality is allowed because it would not improve the position of worst off group. In Rawls’s original graph, going to the right of point a would mean gains for the people in X1 but losses for the people in X2. But the difference principle would not allow further gains for the people in X1 even if they did not make the people in X2 worse off. Thus the difference principle forbids moving to the right of point a even if the line were flat (as it is with the red dashes). Inequality either benefits the worst off class or it is not permitted at all.

Waldron thought the most important arguments for the difference principle are the ones about finality and stability. The idea is that the parties in the original position would reject utilitarianism because they are told their decision must be final and that people would be motivated to comply with the rules. If you are a loser in a utilitarian society, Rawls said, you would find it difficult to comply with the rules and, since the parties know this, they would reject utilitarianism in favor of Rawls’s principles.

Waldron’s point was that a society that met the social minimum could accomplish the same goal. Such a society would ensure that people were comfortable enough that they would not find it difficult to comply with its rules. But it would not be committed to doing more than that.

Aaron asked how the parties in the original position are supposed to take envy into account. We know they are not motivated by envy because Rawls said so. But they have to know that the real people they represent are motivated by envy. That is, presumably, at least partly why inequality would raise problems having to do with the finality of the agreement and the stability of the society. We had to leave this one unresolved.

We spoke a lot about whether relative comparisons are a cause of social instability. Helena surmised that they might be: the poor see what is possible when they see the rich and ask why they have to put up with being poor. Shannon noted a countervailing tendency: inequality can give you an incentive to work rather than rebel.

We talked a bit about the US. Semassa and Austin disagreed about something, but I don’t remember what. Sorry guys! Samuel brought up the riots in Baltimore. Aaron suggested that they are driven by lacking something on the list of absolute needs: security, specifically, security from the police. Hobbes is always lurking around the corner.

Rawls maintains that inequality that does not benefit the worst off is unjust. There are other reasons to care about inequality even if you are not convinced by that.

For instance, if you share Shannon’s opinion that social mobility is desirable, you will want to limit inequality. If the gap between one class and another is too large, it will be very difficult for people to move from the one to the other.

We briefly touched on the political ramifications of inequality last time. The wealthy obviously have more political influence than the poor so a society committed to political equality will want to limit economic inequality.

And there are also social ills that stem from too much inequality, as it is more difficult to establish social relations across wide economic gaps.

There are surely other reasons to care about inequality as well as reasons to worry about the steps typically proposed to reduce it. My point is that there are a lot of things to be said about inequality that are independent of Rawls’s theory. He is the most egalitarian author we have read, but there are reasons for and against egalitarianism that fall outside of his system. Rawls wrote a big book, but the social world is vastly larger.

Mill said our common sense ideas about justice are hopelessly unsystematic. Utilitarianism, he concluded, is the only hope of putting them into any order. Did Rawls show that Mill was wrong?

The original position looks like a serious advance in bringing a system to our ideas about justice. In my opinion, asking “would you approve of X if you didn’t know whether you would be favored or disfavored by X?” is a powerful question. That’s a big deal. At the same time, you might reasonably ask whether the various conflicts among our ideas about justice that Mill pointed out had really been resolved or if the original position largely diverts our attention from them.

And even if the original position is as big a theoretical advance as it appears to be, there’s still the question of whether the parties in the original position would favor Rawls’s principles over utilitarianism. Speaking for myself, I think it’s a very close call.

Hey, if the answers were obvious there wouldn’t be a point to talking about the questions!

Rawls, John. 1999. A Theory of Justice. Revised edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Waldron, Jeremy. 1986. “John Rawls and the Social Minimum.” Journal of Applied Philosophy 3 (1): 21–33.