Our Discussion

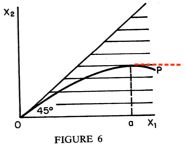

Etelle and Matthew noted that the distribution favored by Rawls’s difference principle is not necessarily a Pareto efficient distribution. We can see this by imagining that the OP curve flattens out to the right of a.

If the OP curve looks like this, then it would be possible to make x1 better off without making x2 worse off by moving along the red dotted line to the right of a. That would be a Pareto improvement over a.

However, the difference principle requires a society to go no further to the right than point a. This is because all inequalities have to work to the advantage of the worst off class and, in this case, the greater inequality that comes from moving x1 further to the right does not benefit x2.

Will asked whether Rawls had much to say about what would be involved in moving from a society like ours, where the distribution of goods and opportunities is well to the right of point a to the difference principle. That will not involve Pareto improvements since, it is pretty likely, some people will have to lose in order to get from where we are to a distribution that satisfies the difference principle. I think Rawls would be comfortable with that; he doesn’t think that Pareto efficiency is tremendously important. But he also does not really have very much to say about transitional questions like the one Will is raising. This bothered Etelle. Matthew, on the other hand, thought it was fine for Rawls to specify an ideal, even if the project of explaining how we could reach the ideal is left for a later date.

Aaron reminded us of a radical criticism of Rawls’s approach. Rawls assumes that economic incentives are necessary for increasing the supply of goods in a society. People won’t work if they won’t be rewarded for their work. A society that is committed to strict equality wouldn’t be able to give those who work more than those who do not. So a productive society has to be willing to tolerate inequality.1 Radical critics note that we all respond to non-economic incentives: parents do not care for their children because they get paid, academics pursue the truth for its own sake, and so on. They theorize that society as a whole could be organized around non-economic incentives. At the very least, I think this shows that in drawing OP the way he did, Rawls was assuming that economic incentives are necessary to motivate productive activity without having proved that this is so.

Finally, Nico and Professor Brown, each in their own way, noted that people might care about their place in the hierarchy, even if that comes at the expense of having a larger absolute amount of wealth and opportunity. Nico mentioned envy and Prof. Brown drew the OP curve so that it crossed the 45 degree line, making x2 the more favored class, before crossing back to reach its maximum height with x1 as the class that is better off.

Having thought about it, I have a couple things to say about these last points.

First, I believe that Rawls thought it was just irrational to care about one’s place in the social hierarchy. If you could be wealthier in the second tier than you would be in the first tier, you should prefer life in the second tier. That’s a debatable point, of course, especially because people often have the opposite preference.

Second, Rawls’s figures feature society’s indifference curves. The idea is that a just society should favor point a on the OP line. From society’s perspective, I can see how it doesn’t matter who is where in the hierarchy. Someone has to be in the first rank, someone else in the second, and so on. They’re all equally members of society, so there is no reason, from the perspective of the society, to think that one should be favored over the others.