Rawls’s Difference Principle

Overview

Here is how today’s reading fits into Rawls’s theory.

Rawls’s goal was to establish a theoretically rigorous alternative to utilitarianism. It is easy enough to come up with apparent exceptions to the utilitarian principle, but it is difficult present a unified alternative. Rawls’s theory is that the way to identify the fundamental principles for society is by asking what the parties in what he calls the original position would prefer. And he maintained that they would choose his two principles of justice instead of utilitarianism.

What is a “party in the original position” and why might you care what such a thing thinks? The parties in the original position represent every member of society with a twist. The twist is that they don’t know who they represent or any other facts that could bias their decisions. The idea is that their decisions are guaranteed to be fair. You would care only if you cared about fairness. Rawls believes that nearly everyone does.

In the reading for today, Rawls explains exactly what his two principles mean. This is completely independent of the main theory about what the parties in the original position would decide, but it is tremendously interesting in its own right. In particular, Rawls confronts some genuine difficulties with equal opportunity that our other authors have neglected.

What Rawls means

Rawls’s principles govern what he calls the basic structure of society. He’s concerned with institutions, such as the education system, legal system, tax system, central banking system, and so on. So none of this is about what individuals should do. It’s about how society’s institutions should work.

Rawls measures the welfare of the members of a society by their share of what he calls primary social goods. Primary social goods are goods that are needed to realize any rational plan of life. Money, for instance, is a primary social good.

Rawls believes that individual liberties and the right to vote should be distributed equally: everyone should have the same liberties and votes as everyone else.

Jobs and incomes will be unequal. Rawls assumes that any society would require at least some degree of inequality. For instance, a society that lets people keep a disproportionate share of what they make will be more productive than one that redistributes everything equally. This is so because people will work harder if they get to keep more of what they create through work. Since inequality is necessary for societies to be wealthy, he assumes all societies will have inequality.

Things that are distributed unequally, like jobs and incomes, are governed by two principles: fair equality of opportunity and the difference principle. Fair equality of opportunity means that every member of society has the same opportunity to get the best jobs as everyone who has the same natural talents; no one’s life will be determined by the social class of their parents. A society satisfies the difference principle if the inequalities in primary social goods maximally benefit the worst off class.

Prioritarianism

Patrick asked if the difference principle is equivalent to what is called “prioritarianism.” I had to look up the latter. This seems to be a fair statement of the view.

Prioritarianism holds that the moral value of achieving a benefit for an individual (or avoiding a loss) is greater, the greater the size of the benefit as measured by a well-being scale, and greater, the lower the person’s level of well-being over the course of her life apart from receipt of this benefit. Well-being weighted by priority as just specified is sometimes called “weighted well-being.” To this account of value the prioritarian adds the position that one ought to act, and institutions should be arranged, so as to maximize moral value as defined. (Arneson 2013)

The difference principle certainly shares the spirit of prioritarianism insofar as both say that society should favor those who are worse off when their interests conflict with those who are better off.

The difference principle differs from prioritarianism in two ways. First, it gives absolute priority to the worst off class rather than simply adding weight to their interests. Second, it says nothing about how to compare benefits to different groups where the worst off would not be affected.

Three cheers for PPE

As I was driving home after class, I was thinking about how awesome Prof. Brown’s presentation was and it occurred to me that I should make explicit something that I have been saying obliquely throughout the term.

I understand philosophy much better than I otherwise would have thanks to teaching the PPE senior seminar.

Let’s review.

Locke: I did not know what to make of the last two-thirds of the chapter on property and willfully ignored it. Now I understand the whole thing.

Dworkin: I struggled mightily with this article in graduate school and, left to my own devices, I would never have looked at it again. Now I feel that I have mastered it.

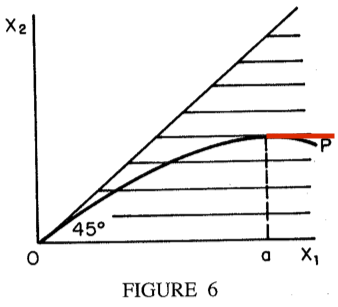

Rawls: even very famous philosophy professors who I will not name could not explain those figures to me. I certainly could not explain them to anyone else. Now I can not only say what is going on but I can explain the origins of the parts that make them up. And you can too!

It is sometimes, oh, who am I kidding, often said that PPE involves sacrificing depth of knowledge for breadth. The point is not that those who take more courses in a particular discipline will have spent more time on the subject than those who have taken fewer courses. It is that those who take more courses in a discipline will understand it better than those who have taken fewer courses. There is some truth to that. Most of us have to practice and repeat things in a subject in order to master it. That said, my experiences have convinced me that the link between depth and understanding is weaker than it is thought to be. Indeed, I think that what passes for deep study of a field can hinder your understanding of that very field.

I have studied philosophy in more depth than any reasonable person would. I have certainly taken more philosophy courses than any undergraduate would. I have taught more philosophy courses than any undergraduate would ever take. Depth? I’m there.

Nonetheless, I did not fully understand the philosophical works that I studied in such great depth until I started doing PPE. In some cases, I taught the material that I did not fully understand. Indeed, it was taught to me by professors who, I strongly suspect, did not fully understand it either. That’s what sticking to your discipline gets you.

There is no shame in this, by the way. Philosophy is hard and I will go to my grave not understanding many things. That’s what makes my job fun even after all these years: there is still so much to learn. But it would genuinely be shameful to ignore all the great work that has been done in other disciplines.

Sometimes, depth just means you are sitting in a hole.

References

Arneson, Richard. 2013.

“Egalitarianism.” In

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta,

Summer 2013.

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/egalitarianism/; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Rawls, John. 1999. A Theory of Justice. Revised edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.