Rawls on Libertarianism

Overview

Rawls walks his readers through a series of four systems for

distributing wealth and opportunities. These systems are defined by how

they combine two different interpretations of two phrases in Rawls’s

second principle of justice. Two phrases that each have two

interpretations yields four systems.

So we get yet another two by two box. I promise that this is

the last one.

The box presents four systems. These systems are defined by how they

interpret two terms in Rawls’s second principle of justice.

Second: social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that

they are both (a) reasonably expected to be to everyone’s

advantage, and (b) attached to positions and offices open to

all.” (Rawls 1999,

53, italics added)

If you put the two interpretations of the phrase “to everyone’s

advantage” in the columns and the two interpretations of “open to all”

in the rows, this is what you get (Rawls 1999, 57).

|

Principle of efficiency |

Difference principle |

| Equality as careers open to talents |

System of Natural Liberty |

Natural Aristocracy |

| Equality as equality of fair opportunity |

Liberal Equality |

Democratic Equality |

Why Democratic Equality is the best

The idea of this box is that no matter where you start, you will wind

up with Democratic Equality. Rawls starts in the northwest box, with the

System of Natural Liberty.

The System of Natural Liberty is the one that most resembles Nozick’s

libertarianism. Rawls thinks that this is consistent but wrong. He

believes that it is unfair for the course of your life to be determined

by social factors, like your family’s class, or natural factors, such as

your abilities. These things, he believes, are “arbitrary from a moral

point of view” (Rawls

1999, 63). The System of Natural Liberty does nothing to correct

or compensate for either the social or the natural causes of

inequality.

The systems in the southwest and northeast boxes make partial

attempts to deal with the problem of morally arbitrary influences on our

lives. Rawls argues that they are inconsistent. If you think you should

move from the System of Natural Liberty to either Liberal Equality or

Natural Aristocracy, then you will wind up moving to Democratic

Equality.

Liberal Equality, the southwest box, seeks to correct the social

causes of inequality. It does so with an educational system that seeks

to ensure that everyone has the same opportunities in life as those with

similar natural talents, regardless of their social background. As Rawls

puts it, “those who are at the same level of talent and ability, and

have the same willingness to use them, should have the same prospects

for success regardless of their initial place in the social system”

(Rawls 1999,

63).

Natural Aristocracy does nothing to correct for the social causes of

inequality but it compensates those who have less by implementing the

Difference Principle. The Difference Principle holds that inequalities

in wealth and opportunity are allowed only if they improve the wealth

and opportunities of the worst off class.

Rawls believes that Liberal Equality and Natural Aristocracy are

unstable compromises. If you are convinced that the distribution of

goods should not be influenced by morally arbitrary factors, why address

only some of those factors rather than addressing them all as Democratic

Equality does? Someone who moved from Natural Liberty to one of these

other systems would not stay there because the line of thinking that

leads away from Natural Liberty also leads beyond them. Thus, Rawls

concludes, only Democratic Equality is both consistent and correct.

What is the Difference Principle?

The Difference Principle holds that a society should allow inequality

in wealth if and only if that inequality works to the advantage of the

worst off class. The idea is that people will produce more only if they

are allowed to keep at least part of what they produce. The poorest

people, in turn, are better off living in a more productive society that

is unequal than they would be in one that was strictly equal. They

benefit from the greater production that follows from inequality. So the

Difference Principle allows inequality because it makes everyone better

off. But it only allows inequality so long as the worst off benefit.

Once greater inequality ceases to benefit the worst off class, it is no

longer allowed; it would be confiscated by taxes or discouraged by

regulations.

One way to put it is that the Difference Principle is the most

rational form of egalitarianism because it allows inequality when

inequality benefits the people at the bottom.

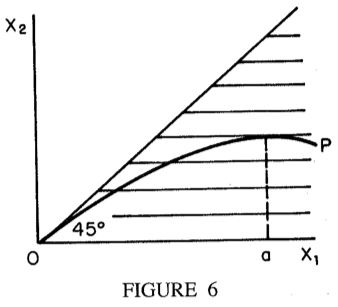

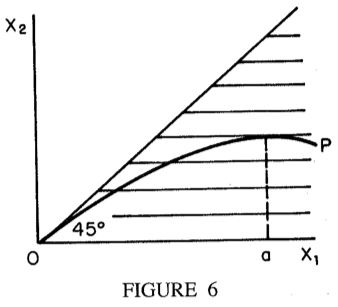

This figure illustrates how the Difference Principle works.

The two axes represent wealth that goes to representative members of

different classes: X1 and X2.

The origin represents what society would produce if wealth were

distributed equally between those classes. It is not nothing; it’s just

where the graph starts.

The curved line (OP) represents what society could produce

if it allowed inequality. X1 gets wealthier as the OP line

goes to the right and X2 gets wealthier as the OP line goes

up. In this case, the X1 class gets more wealth than the

X2 class. That is why the curved line is below the 45 degree

line: it moves more to the right than it moves up.

When the OP line is moving up and to the right at the same time, both

X1 and X2 benefit. A society following the

Difference Principle would seek to hit point a. That is where

the OP line reaches its highest point on the Y axis, meaning that is the

point where inequality benefits the members of the worst off class the

most. Anything to the left or right of a would leave people

like X2 worse off than they would be at point a.

Why does society produce more with inequality?

The OP line assumes that society will have more resources if it

allows inequality than it will if it insists on strict equality. That’s

why the OP line moves to the right and up from the origin.

Why does Rawls think that assumption makes sense? It is basically for

the same reason Locke gave in his theory of property rights: if people

have rights over what they produce, they will produce more than they

would if they do not have rights over what they produce. A society that

insists on strict equality would distribute anything extra that an

individual makes among everyone. So the individual’s incentive to

produce anything extra would be minuscule. By contrast, if you allow

people to keep a substantial portion of what they make, they will make

more stuff. That is why Rawls drew the OP line as he did.

What Would a Libertarian Say in Response?

This is Rawls’s only significant discussion of libertarianism and it

comes in the informal part of the book. By “informal,” I mean the part

where he took himself to be explaining his ideas rather than arguing for

them. The official arguments come later; they depend on what the parties

in the original position would choose.

The parties in the original position are not asked to consider

libertarianism. The part that we talked about today gives Rawls’s

reasons for not asking them to consider libertarianism.

If I were Nozick, I would say that Rawls’s assumption that society

should be concerned with the morally arbitrary influences on life is

wrong and that the unfairness of life is only a metaphorical expression.

As Nozick sees it, only people can be unfair. No one treats you

unfairly if you do not succeed because you lack talent and it is not

unfair for parents to favor their children. So, in Nozick’s opinion,

neither the natural nor the social sources of inequality are necessarily

unfair or morally arbitrary.

That, in my opinion, is the argument that Rawls has to beat.

What Would a Radical Critic Say?

If I were a radical critic of capitalist society, one thing I might

do is question Rawls’s assumption that inequality is necessary for a

productive society.

In Figure 6, the line OP represents what a society could produce. The

origin represents the goods available in a perfectly equal society. (It

is at coordinate 0,0 on the graph, but that does not mean it is nothing;

it’s just where the graph starts.) The amount of goods rises (it moves

up and to the right) as more inequality is allowed (the OP line moves

away from the 45 degree line).

The assumption is that people will produce more if and only if they

are allowed to keep at least a part of what they make. That is why you

get inequality: the more productive wind up with more than the less

productive do.

But a radical critic might question whether this is really so. Could

people be motivated to produce for reasons other than gain? Could they

be motivated by artistic reasons, social solidarity, or something else?

It may be true that incentives are needed to motivate people to work in

our society. But, a radical critic may say, that does not mean

that all societies must work this way. In a different social

order, people would have different motivations.

Speaking for myself, I think Rawls is probably right. But he hasn’t

shown that he is right. He has just drawn a graph that

assumes that inequality is necessary for a productive

society.

Do People Keep What They Make?

Suppose you think that people who work harder (or more productively)

should get more than those who do not. That is something that most of us

believe. Rawls agrees, in a way. People like X1 have more

because they produce more for society while people like X2

have less because they produce less.

But Rawls is unlike Locke in the following way. He does not think

that there is a natural relationship between working and having rights

to keep what you produce. People like X1 get to have more

because giving them more works to the advantage of the worst off class.

When letting them keep what they produce no longer benefits the worst

off class, they no longer get to do so. In that way, Rawls’s views are a

bit like utilitarianism. Your economic rights are derived from

considerations of the social good; they are not natural rights.

Does Everyone Have to Work?

The Difference Principle requires a society to maximize the resources

going to the people in x2 regardless of why they are

worse off than the people in x1. The graph says nothing about

why people wind up where they do in the income distribution.

It does not matter if the people in x2 are worse off due

to factors beyond their control or if they are just lazy and

deliberately choose not to work because they know they are guaranteed to

wind up at point a.

I think it’s obvious why some people would find this objectionable.

But when we talk about the Original Position, you will see why the

parties do not care. They do not have any more opinions and so they do

not find laziness or cheating bad. They just want to protect their

interests. And for all they know, they represent people who just do not

want to work. They have to protect people like that.

Why Not Natural Aristocracy?

Rawls thinks the equal opportunity should come before the difference

principle. That means that he thinks society should devote its resources

to ensuring that “those with similar abilities and skills should have

similar life chances” (Rawls 1999, 63). Only once it has

achieved this goal will it use the resources it has left over to make

the position of the worst off class as good as it can be.

Of course, the two projects often go together. A society can raise

point a by developing the talents of its members so that they

are more productive. So a society devoted to the difference principle

will also do quite a lot to counteract the influence of social class on

the development of talents.

But equality of opportunity as Rawls understands it is very

demanding. At some point, I suspect that the resources needed to move a

society closer to equal opportunity would go to the educational system

at the expense of improving its productive capacity.

A Natural Aristocracy follows the difference principle: it seeks to

make the people at the bottom as well off as they possibly can be

without being committed to equal opportunity. I think this makes more

sense for Rawls. When spending on the educational system does not

improve the productive capacity of society, a Natural Aristocracy will

stop putting money into it. But a society devoted to equal opportunity

will keep going: it will devote resources to the educational system

until equal opportunity is achieved, even if that comes at the expense

of transferring wealth the the poor. In my opinion, Rawls made a better

case for the difference principle than for equal opportunity.

Why? Well, Rawls himself argued that the distribution of natural

talents, abilities, and skills is “arbitrary from a moral point of view”

(Rawls 1999,

63). Why should it matter whether your success or failure is due

to natural or social causes? If you fall to the bottom class in society

because you have little natural talent or because your society did not

develop your talents, it should all be the same from the “moral point of

view.” Neither one is more fair or unfair to the person behind the

talents. So the only thing left to do would be to ensure that those at

the bottom have as much as possible.

Here is Milton Friedman making the same point.

Inequality resulting from differences in personal capacities, or from

differences in wealth accumulated by the individual in question, are

considered appropriate, or at least not so clearly inappropriate as

differences resulting from inherited wealth.

This distinction is untenable. Is there any greater ethical

justification for the high returns to the individual who inherits from

his parents a peculiar voice for which there is a great demand than for

the high returns to the individual who inherits property? …

Most differences of status or position or wealth can be regarded as

the product of chance at a far enough remove. The man who is hard

working and thrifty is to be regarded as ‘deserving’; yet these

qualities owe much to the genes he was fortunate (or unfortunate?)

enough to inherit. (Friedman [1962] 1982, 164–66)

I am not saying that I am opposed to equal opportunity. My point is

only that I do not think Rawls has an explanation of why equal

opportunity is valuable and, in fact, his arguments undercut the case

for thinking that it matters. The point is about what the arguments

show, not about my own moral beliefs.

That said, I do think that giving absolute priority to equal

opportunity when compared with improvements for the welfare of the less

talented is unwise. Why should society always

give priority to securing opportunities for the naturally talented over

improving the welfare of the less talented? Suppose, for instance, that

society has to choose between improving the quality of life for

intellectually disabled people and making sure everyone can afford to go

to the best college they can get into. Should it always choose the

second?

Main points

Here are the terms and concepts you should know or have an opinion

about from today’s class.

- Rawls’s four systems: Natural Liberty, Liberal Equality, Natural

Aristocracy, Democratic Equality.

- What Rawls means by “factors so arbitrary from a moral point of

view” (Rawls 1999,

63).

- Figure 6 and the Difference Principle.

Jefferson, Harvard, and Natural Aristocracy

I am reasonably sure that the term “Natural Aristocracy” comes from

Thomas Jefferson; I will document this below. However, for Rawls, the

source would have been James Conant,

the President of Harvard between 1933 and 1953.

Though today’s high school seniors may find it hard to believe,

Harvard, Yale, and other leading universities weren’t exactly bastions

of the best and brightest before World War II. They educated primarily

the progeny of the upper class—white, Protestant, male students, the

products of New York and New England private schools, who were often

more interested in debutante cotillions and sporting events than in the

life of the mind. Many brought servants with them to Cambridge and New

Haven.

James Bryant Conant, the president of Harvard University and one of

the most influential men of his day, wanted to replace this aristocracy

of birth and wealth with what Thomas Jefferson called a “natural

aristocracy” of the intellectually gifted from every walk of life, who

would be educated to high standards and then be given the responsibility

of governing society. The creation of what Conant called “Jefferson’s

ideal,” a new intellectual elite selected strictly on the basis of

talent, and dedicated to public service, would, he believed, make

America a more democratic country.

In 1933, he gave two Harvard administrators the job of developing a

nation-wide scholarship program for gifted students. The key to the

administrators’ work would be the creation of a single standard for

evaluating the astonishing diversity of the country’s high-school

students. And the test Conant ultimately selected for that purpose—the

newly developed Scholastic Aptitude Test—would become for many students

a narrow path to the best opportunities—and richest rewards—in American

society. (Toch

1999)

A natural aristocracy selects those who are the most talented,

regardless of their social class, for universities and then, presumably,

leading positions in society. Rawls finds this deficient because it does

not take any effort to develop the talents of children in lower class

families. It just selects those whose talents are observable in late

adolescence.

I do not think that Rawls thought through the differences between

his definition of “Natural Aristocracy” and what Jefferson and

Conant meant. The natural aristocracy in the northeast corner of Rawls’s

box includes the difference principle, so any inequalities favoring the

natural aristocrats in his system would have to be to the advantage of

the worst off class.

As for Thomas Jefferson, here is his reply to a letter

from John Adams. Adams offered his interpretation of a passage from

Theognis as meaning, roughly, that people will prefer to marry into the

families of rich bad people over poor good ones. The result, Adams

fears, is that society will be ruled by wealth and birth rather than

talent and virtue.

Now, my Friend, who are the αρiςτοι [aristoi]? Philosophy may Answer

“The Wise and Good.” But the World, Mankind, have by their practice

always answered, “the rich the beautiful and well born.” And

Philosophers themselves in marrying their Childen prefer the rich the

handsome and the well descended to the wise and good. What chance have

Talents and Virtues in competition, with Wealth and Birth? and

Beauty?

Jefferson’s

reply notes that Theognis’s proposal to engage in selective breeding

of human beings would be rejected in a society that believes in “the

equal rights of men.” (Whew.) Consequently, he says, we will have to

“content ourselves with the accidental aristoi produced by the

fortuitous concourse of breeders.”

Jefferson thinks this will be acceptable because there is a “natural

aristocracy” based on talent that can offset the “artificial

aristocracy” of inherited wealth.

For I agree with you that there is a natural aristocracy among men.

The grounds of this are virtue and talents. Formerly bodily powers gave

place among the aristoi. But since the invention of gunpowder has armed

the weak as well as the strong with missile death, bodily strength, like

beauty, good humor, politeness and other accomplishments, has become but

an auxiliary ground of distinction. There is also an artificial

aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or

talents; for with these it would belong to the first class. The natural

aristocracy I consider as the most precious gift of nature for the

instruction, the trusts, and government of society. And indeed it would

have been inconsistent in creation to have formed man for the social

state, and not to have provided virtue and wisdom enough to manage the

concerns of the society. May we not even say that that form of

government is the best which provides the most effectually for a pure

selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of government? The

artificial aristocracy is a mischievous ingredient in government, and

provision should be made to prevent its ascendancy.

The letter ends with what is really at issue between them, namely,

how to design political institutions to blunt the power of the

artificial aristocracy while advancing the natural aristocrats. Adams

seems to have favored something like the English House of Lords (a weak

Senate, I assume) while Jefferson thought that the citizens in a

democracy would select the natural aristocrats over the artificial

ones.